Hendrika' Blog

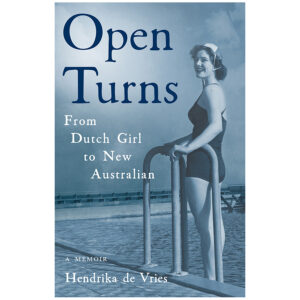

Happy to Announce My New Book

Dear friends, This is a huge “thank you” to all of you who read When a Toy Dog Became a Wolf and the Moon Broke Curfew,...

Read MoreAs 2024 turns into 2025…

“I don’t know how I am going to face this next year,” a friend told me recently. She is not the only one with a heavy...

Read MoreNews Flash

That little toy war dog just keeps winning awards! Dear Friends, I am thrilled to share that my memoir When a Toy Dog Became a Wolf...

Read MoreAudiobook Now Available

I am thrilled to announce that my memoir, When a Toy Dog Became a Wolf and the Moon Broke Curfew, is now available in audio format....

Read MoreA New Year’s Eve Miracle

May the New Year bring the “miracle” you wish for. We walked with deliberate steps. Placed our feet with careon the slippery surfaceof the ice-covered sidewalks...

Read MoreEaster reflections in the time of COVID-19

I have found one of the lovely surprises about growing old if you are lucky, is that you become part of a web of friends, colleagues and...

Read MoreA Mother’s New Year’s Wish and Intention

On December 31, 1960, I “missed a great New Year’s Eve party,” so my then-husband told me, because I had just given birth to our second...

Read MoreToy Dogs and Moons Give Thanks

It takes one person to tell her story. It takes a village to hear its meaning and give it wings. As we approach this North American Holiday...

Read MoreSharing Our Stories

Shining a Light (Published in Women Writers, Women‘s Books, August 27, 2019.) From the time that I was a little girl curled up on my father’s...

Read More